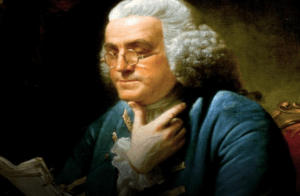

Benjamin Franklin, Patriot or Spy?

The question of whether Benjamin Franklin was a patriot or a spy is a topic of historical debate that has intrigued scholars and historians for centuries. Franklin, a prominent figure in American history, played multifaceted roles during the American Revolution and the early years of the United States, making it challenging to categorize him simply as a patriot or a spy.

First and foremost, Benjamin Franklin was unquestionably a patriot. He was a key Founding Father and played a pivotal role in shaping the American Revolution and the formation of the United States. Franklin’s contributions were wide-ranging, from his diplomatic efforts in securing French support for the American cause to his role in drafting essential documents like the Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution. His commitment to the American cause is evident in his tireless efforts to secure independence from British rule.

However, the notion of Franklin as a spy is more complex. While Franklin engaged in covert intelligence gathering, especially during his time as the American ambassador to France, his primary role was that of a diplomat and statesman. Franklin did use his extensive network of contacts to collect information that could benefit the American cause, but he did so in a manner consistent with the diplomatic practices of his time.

Franklin’s intelligence-gathering activities in France, while not necessarily espionage in the modern sense, were undoubtedly instrumental in facilitating American success during the Revolutionary War. He leveraged his charm, wit, and intellect to cultivate relationships and gather information that proved valuable in negotiations and strategy.

In conclusion, Benjamin Franklin’s legacy as a patriot is well-established, and his contributions to the American Revolution and the founding of the United States are undeniable. While he engaged in some intelligence-gathering activities, it is more accurate to view him as a patriot who used his diplomatic skills to advance the cause of American independence. Franklin’s complex and multifaceted role in history defies simple categorization as either a patriot or a spy, highlighting the nuanced nature of his contributions to the American Revolution and the early years of the nation.

Famous British Historian Claims Benjamin Franklin Was A British Spy

By Richard Deacon, author of “A History of the British Secret Service,” as told to Tom McMorrow.

(Originally published in Argosy magazine, July 1970, pp. 34 ff).

England’s infamous Hell-Fire club, a band of orgy-loving rakes, doubled as the center of British espionage during the American Revolution. According to the author’s evidence, Franklin was a member in good standing known to the British Secret Service as “Agent No. 72.”

IF GEORGE WASHINGTON was the father of our country, Benjamin Franklin is at least entitled to be considered its uncle. Every family has its grand old Uncle Ben – not stern and austere like Father George, but a puckish old knee dandler who invents things, has traveled to exotic lands and is whimsically wise in counsel.

Such is the image of Benjamin Franklin, statesman, philosopher, scientist and framer of our Declaration of Independence. As portrayed on the Broadway stage in the inspired musical drama, “1776,” he wins ovations at every performance and sends the audience home feeling warmed and re-Americanized.

And if, in his vintage years, this colorful old uncle entertained a grand-nephew or grand-niece with tall tales of the days when he was Agent 72 of the British Secret Service, how they must have goggled and gasped.

One can see the children’s mother, smiling tolerantly and shaking her head, arms akimbo: “Oh, Uncle Ben, how you do go on! You’ll have them believing those stories!”

And the old gentleman wheezing, “Harmless fantasies, dear niece, designed to entertain the childish mind,” and re-lighting his meerschaum with a taper, the shadow of a smile playing about his lips.

Benjamin Franklin, an agent of the British Crown? That homespun Philadelphia philosopher? One might as well call Whistler’s Mother a Madam.

If that be so, Madam Whistler it is, henceforward, because the Honorable Mr. Franklin was referred to in dispatches of the British Secret service during the Revolution as “Number 72.”

In doing research for his book, “A History of the British Secret Service,” the co-author of this article uncovered that almost unacceptable fact in the Service’s eighteenth-century records.

Standing alone, such a statement would be unworthy of publication, but the discovery of this startling bit of intelligence has led to a re-examination of all possibly pertinent documents in search of corroborating or contradictory evidence, and every fact turned up points to one conclusion: Benjamin Franklin was a double agent, working hand in hand with the British arch-spy, Edward Bancroft, during the Revolutionary years when he was America’s Ambassador to France.

“So great is his [Franklin’s] reputation, that almost no modern writer has undertaken to question the uprightness of his actions, or failed to accept his testimony at face value,” wrote T.P. Abernethy in his account of the controversial relationship between Franklin and Arthur Lee of his Embassy. “Such historical practice is, of course, not justifiable.”

Abernethy went on to counsel “a discarding of hero worship,” and to suggest that “a careful weighing of all contemporary evidence would produce a conclusion quite different from that which has been reached.”

The scholar did not, however, pursue such evidence further, and his wise admonition has, like most good advice, been respected and generally ignored ever since.

The only research done on the subject in recent years has been on the part of various American university professors, out to disprove the / 36 / allegation that Franklin belonged to the notorious Hell-Fire Club in London in the early 1770s. They failed to reach a firm conclusion, and the evidence on the British side of the Atlantic points conclusively to his membership in the strange secret society.

Let us open the presentation of our case by listing the documented associations and other items of evidence that go to support our contention that the author of such prim homilies as “Early to bed and early to rise makes a man healthy, wealthy and wise” was much more than the “rustic philosopher” a leading encyclopedia calls him – was, indeed, a master of international intrigue and espionage:

Close friendship with Lord le Despencer, founder of Hell-Fire, a society of libertines which British Intelligence used as a cover.

Use of the pseudonym, “Brother Benjamin of Cookham.”

Association with the Chevalier d’Eon de Beaumont, a spectacularly successful French secret agent (who usually posed as a woman).

Membership in a firm of land speculators chartered by the British Government, retained during the Revolution.

Protests by both French and American diplomats that every move of the Americans in Paris during the Revolution was known by the English Ambassador.

Existence inside Franklin’s American Embassy of a cell of British Intelligence agents organized by his chief assistant, Bancroft.

The fact that copies of most of Franklin’s reports to America during the Revolution are in the British Archives.

Certain memoranda from the British diplomat, Richard Oswald, from Paris to his government in London.

Franklin’s rejection of espionage charges against Bancroft – a man characterized by King George III himself as a double agent – refusal to investigate those charges and denunciation of the man who made them.

Documents in the British Museum revealing that Franklin passed on to London information about American shipping.

John Adams, whose theatrical shade capers nightly on the Broadway stage in a comic dance with Franklin and Thomas Jefferson in “1776,” either was not that chummy with old Ben, or soured on him during the Revolution, as attested by his words at the time of the peace negotiations: “Franklin’s cunning will be to divide us; to this end,, he will provoke, he will insinuate, he will intrigue, he will maneuver.”

Before we proceed into documentation of these charges, it were well that those who may be distressed at them, or disturbed that they should be published at all, take a moment to consider – with all the awesome respect that was due him – the man against whom they are made.

This was no two-dimensional figure out of a fairy tale or a television series, but one of the greatest intellects known to history. And if he acted as a law unto himself, let it be considered that he was a poor tradesman’s son, attended school only two years and was working in a shop at twelve: but in later life, when in the company of such men as George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, all cultured aristocrats and future presidents, he was the most accomplished among them.

With virtually no schooling, he had taught himself several foreign languages, science and mathematics, and was publishing “Poor Richard’s Almanack” by the time he was twenty-six. He authored the definitive work of the time on electricity, swayed the British Parliament with his oratory to levy taxes on the sons of William Penn and to repeal the Stamp Act, was honored by the Universities of Yale, Harvard, Oxford and Edinburgh, the Royal Society of Britain and the Royal Academy of Science in France.

In Paris, where he was an intimate of Voltaire and the darling of the doomed court of Louis XVI, he scored possibly his greatest triumph, persuading the French to enter the war on the side of the Colonies.

If a humble candle-0maker’s son had the intellect to rise to such stature among men and nations, and did not in the process pick up a considerable amount of arrogance, no matter how diligently disguised, he would be a saint and not a man.

And Ben was indisputably a man. Consider this, from his pen, in 1748, when he was thirty-nine:

“Fair Venus calls; her voice obey;

In Beauty’s arms spend night and day

The joys of love all joys excell

And loving’s certainly doing well.”

Yes, the Presbyterian moralist undeniably enjoyed the pleasures of the flesh as a man of his giant vitality must be expected to, and in that connection the question of his membership in the Hell-Fire Club arises.

The society was founded by Lord le Despencer, better known under his previous title of Sir Francis Dashwood, briefly Chancellor of the Exchequer and a notorious rakehell. It was muttered in the taverns that the members practised black magic, but this was a belief those jaded sophisticates fostered among the ignorant for their own amusement. The rites of Satan worship in which they indulged were in the nature of a hoax and were never taken seriously.

The fraternity, whose members were known as the Knights of St. Francis of Wycombe, had its deadly serious aspect, however. British Intelligence found the setup ideal as a cover for meetings, and its agents gathered at Wycombe periodically in the guise of idle revelers.

In 1773, when he was in England acting as agent for / 60 / the Colonies of Georgia, New Jersey and Massachusetts, Franklin wrote to his son in America:

“I am in this house as much at my ease as if it was my own; and the gardens are a paradise. But a pleasanter thing is the kind countenance, the facetious and very intellectual conversation of Mine Host, who, having been for many years engaged in public affairs, seen all parts of Europe, and kept the best company in the world, is himself the best existing.”

That host was Lord le Despencer, the homelike domicile was West Wycombe House, and the gardens Franklin described as paradisiacal were decorated with phallic statuary and laid out in patterns of erotic symbolism so flagrant that a later generation had the entire layout razed to the ground.

West Wycombe Church stood on a hill nearby, and in some caves beneath it, the Hell-Fire Club met, the male members, known as “monks,” dressed in vari-colored habits, the females, or “nuns,” in white habits and masks. A society rule stipulated that the ladies “consider themselves as the lawful wives of the Brethren during their stay within monastic walls.”

“The rites of the Knights of Wycombe,” an historian has said, “were of a nature subversive of all decency.”

Was Ben but obeying the voice of the “fair Venus” he had extolled in rhyme many years before, in his association with the naughty Knights? If so, we should be ashamed to intrude on the old gentleman’s privacy, but then there is the impressive list of high-ranking British officials who were members of the society. It included the First Lord of the Admiralty, the Paymaster-General, a former Prime Minister, three members of Parliament, and former Chancellor of the Exchequer le Despencer. Even Frederick, the Prince of Wales, was reputed to be a member.

The closeness of Franklin’s relationship with le Despencer is further demonstrated by the fact that they co-authored a “Revised Book of Common Prayer” for the Church of England.

Franklin’s satirical wit comes through in their description of the prayer book’s aims: “To prevent the old and faithful from freezing to death through long ceremonies in cold churches, to make the services so short as to attract the young and lively, and to relieve the well-disposed from the infliction of interminable prayers.”

Predictably, the Church of England ignored the book.

Strong evidence of Franklin’s Hell-Fire membership is in a letter he wrote to a Mr. Acourt, of Philadelphia, not quoted by most biographers. He mentions “the exquisite sense of classical design, whimsical and puzzling as it sometimes may be in its imagery, is as evident below the earth as above it.”

This has to be a reference to the subterranean caves in which the club met, and none but a member had ever entered there.

The site of the Hell-Fire Club, before its move to Wycombe, was on the aforementioned island in the Thames. This island lay between Cookham and Marlow, a fact which lends significance to an account of a meeting with Franklin by the painter Giuseppe Borgnis.

According to Borgnis, a London innkeeper, recognizing the distinguished Colonial, asked, “Is that not Master Franklin?”

And Franklin replied with an enigmatic smile, “No, it is Brother Benjamin of Cookham.”

Purely circumstantial? Then consider this. An entry in the society’s wine books reads: “On the 7yth of July, 1773, Brother Benjamin of Cookham: 1 bottle of claret, 1 of port and 1 of calcavello.”

And most damningly, this: Toward the middle of the nineteenth century Lord le Despencer’s illegitimate daughter, Rachel Antonina Lee, told historian Thomas deQuincey that her father, in his last years, would often raise a toast to “Brother Benjamin of Cookham, who remained our friend and secret ally all the time he was in the enemy camp.”

She stated flatly that “Brother Benjamin” was Franklin, and that he “sent intelligence to London by devious routes, through Ireland, by courier from France and through a number of noble personages in various country houses.”

The Hell-Fire member with the most spectacular reputation among the initiate was the Chevalier d’Eon de Beaumont, a French spy as skilled in the devious arts of his profession as any character of fiction.

One of his triumphs was scored when he was sent to the Russian court in the guise of a French noblewoman, the vivacious “mademoiselle Lia de Beaumont.” Not content with deceiving the Russians with his transvestite performance to the point where he was picking up intelligence on court intrigues, d’Eon, with the boldness of a great spy, applied for the post of lady-in-waiting to the Czarina – and got it.

The Philadelphia philosopher and the Chevalier became friends in the early 1770s, when the French master spy was assigned to London, and promptly joined the Hell-Fire club. Recognizing their mutual interest, they maintained close contact through secret intermediaries. D’Eon, who had powerful enemies at court, gave Franklin information on political intrigues in exchange for briefings on French affairs and secret plans to be passed on to the English.

That Franklin tried to serve England (where, as many have forgotten, he spent seventeen years of his life before the Revolution) and the cause of the Colonies simultaneously is pain enough up to 1770. Thereafter, as relations worsened and blundering British generals in America clumsily escalated revolt into a revolution, he merely drew a veil of secrecy over his machinations.

He did not regard this as two-faced or treacherous, but as working out his own grand design for world politics, which he alone among the Colonists could perceive. Roughly, that grand design was that there was room in the future both for a free America and an all-powerful British Empire. To think only of independence would, to his mind, have been both provincial and insular.

As one who had known poverty as a child, Franklin was also intensely acquisitive where land was concerned. In 1760 he had co-operated in the development and organization of a group in England known as the Walpole Association, headed by Thomas Walpole. This became the Grand Ohio Company, and Franklin worked with them until 1777 trying to secure a grant to territory to be named Vandalia in what today is Virginia.

In 1776, just before leaving for France as Ambassador, he was chairman of a meeting of land speculators, all members of the Grand Ohio Company, in Philadelphia. The aim of the meeting was the consolidation of the Vandalia proposal.

And in 1778, two years deep into the Revolution, he was still paying his expenses to the British-chartered Grand Ohio Company, which would have the authority to set up another American colony only if the Revolution were put down.

During the war, he continued to correspond with Walpole and other associates in England, like d’Eon de Beaumont, Lord Shelburne, Lord Camden, Thomas Wharton and John Williams.

The Comte de Vergennes, whose desire for war with England made him one of France’s most enthusiastic supporters of Franklin’s plea for military aid, later found himself complaining that every move by the Americans in Paris was known to the English Ambassador, Lord Stormont. And small wonder, for inside the American Embassy was a cell of British Intelligence, organized by Edward Bancroft, the Ambassador’s chief assistant.

It might be argued that Franklin was duped by his assistant and was merely incompetent in the field of security. / 61 /

So feeble an argument is barely worth refuting. Franklin, who had been in international diplomacy since 1757, when the Pennsylvania Legislature first sent him to Parliament as its representative, was infinitely sophisticated in politics and international intrigues, as has been seen, and moreover, he was constantly being warned that there were leaks from his Embassy.

Arthur Lee, one-time American representative in London and the man who incurred Franklin’s wrath by denouncing Bancroft, caustically charged that no precautions were taken in the Embassy to guard secrets, that “servants, strangers and everyone was at liberty to enter … and that the papers relating to it lay open in rooms of common and continual resort.”

It is inconceivable that Franklin did not know what was going on. A more charitable explanation would be that he was so cynical that he did not think the leakages mattered.

And indeed, in the long run, they did not change the situation. What these leakages insured, and what Franklin’s undercover dealings with the British underlined, was that his standing with London remained high and that in the event of the Colonies failing to win the war, his influence with the English would still be considerable.

As to the question of Bancroft’s guilt, one simple fact proclaims it more loudly than a host of accusations: When this supposed Revolutionary patriot reached retirement age, a grateful British government awarded him a pension of 1,000 pounds a year.

This was the man Franklin defended when Arthur Lee confronted him with proof of Bancroft’s links with the English Secret Service, and evidence that he was in touch with the Privy Council in London. Franklin insisted that Bancroft’s visits to London provided intelligence for America.

The truth was that all Bancroft brought back from these trips was false information provided by the English, as Franklin must have known. And Arthur Lee, who was described by Bancroft himself in a letter to Paul Wentworth as incorruptible and “impossible to bribe,” was not the only prominent man to bring charges against Bancroft. John Adams and Thomas Jefferson made similar accusations against Franklin’s chief assistant, and indeed George III himself said of Bancroft: “The man is a double agent. If he came over to sell Franklin’s American secrets in London, why wouldn’t such a fellow return to France with a British cargo for sale?”

Bancroft’s information was usually passed on to Lord Weymouth or Lord Suffolk, but Franklin kept certain intelligence to himself to pass on personally, via devious routes, to the Franciscans at Wycombe. Evidence of one of these operations is contained in the papers of one John Norris, of Hughenden Manor.

Norris had built a hundred-foot tower on a hill at Camberley, in Surrey, from the too of which he used to signal with a heliograph’s flashing mirror to Lord le Despencer at West Wycombe, to place bets. In those papers, this enigmatic note appears: “3 June,

1778. Did this day Heliograph Intelligence from Dr. Franklin in Paris to Wycombe.”

On other occasions, Franklin’s information was passed to London by direct diplomatic channels, as shown in a letter from Richard Oswald in Paris to Lord Shelburne in London on July 11, 1782. The reference is to peace negotiations. “they have shewn (CQ) a desire to treat and to end with us on a separate footing from the other Powers,” Oswald wrote, “and I must say, in a liberal way, or at least with greater appearance of feeling for the future interests and connections with Great Britain than I had expected. I speak so from the text of the last conversation I had with Mr. Franklin.”

In another memorandum, Oswald wrote that he had been tipped off “in the easy way of conversation with the Doctor,” of an alliance with Spain. This information, he added, was passed on informally, “yet, I imagine, with a view to its being properly markt (CQ) and communicated, also, and most likely, with the same good intentions as on former occasions.”

The most disturbing piece of evidence against Franklin leads to this sober question. Was his policy truly Machiavellian, partly personal and partly political?

The item is in the correspondence of John Vardill, a loyalist clergyman who was a British spy in London. Vardill bribed Joseph Hynson, a seafaring man from Maryland, described as “very close to Franklin,” to betray American dispatches.

The clergyman-spy’s correspondence, which is in the British Museum in London, reveals that Franklin passed on to London information about sailing dates, shipments, and supplies to America, and details of cargoes.

Arthur Lee, whom Franklin described in a letter to Joseph Reed, in 1780, as a man to beware of – “for in sowing suspicions and jealousies .. in malice, subtlety and indefatigable industry, he has, I think, no equal” – gave his Ambassador good cause to speak ill of him. Along with his charges that the Embassy was a nest of spies, he was convinced that Franklin and Silas Dean, former agent for Massachusetts, had used for their own purposes funds provided by the Continental Congress. The Lee Papers reveal this in his letter to Richard Henry Lee, dated September 12, 1778.

Was Franklin contrite in the face of these charges, or did he, indeed, offer any defense of his actions? Not at all. When he returned to America, a Congressional Committee was appointed to examine his accounts, which showed a deficit of 100,000 pounds.

Old Ben’s retort was a classic. “I was taught as a boy to read the Scriptures and to attend to them,” he told the Congressmen in what was doubtless the orotund tones of an eighteenth-century Everett Dirksen, “and it said there: ‘Muzzle not the ox that treadeth out his master’s grain.’”

There was in Franklin’s makeup something of Talleyrand, something of a medieval Pope and even, at his worst, the twisted astuteness of a Pierre Laval. Perhaps the problem was that he was a true citizen of the world in an age of imperialist rivalries which gave him a greater objectivity than that possessed by his contemporaries.

A line from a Franklin essay, “Observations of My Reading History in Library” is more self-revelatory, in view of what we have learned, than he could have intended:

“The great affairs of the world, wars, revolutions, etc.,” he wrote, were conducted by those who, while maintaining the public interest, “acted from selfish interests, whatever they may pretend.”

http://chss.montclair.edu/english/furr/fc/deacononfranklin.html